Chapter 8:

Museums are good to think with

What happens when two visitors come to a museum to see an exhibition? Is it pure experience and identification or do they learn something? This chapter discusses the two main components of the encounter between the visitor and the museum. One component is the framework of possibilities the exhibition offers and the other is the Exhibitions offer physical and mental input that allows visitors to design and develop the opportunities available in an exhibition, but visitors also come with previous knowledge, motivation and immediate interests. An exhibition is like a Chinese box where the framework of possibilities of the exhibition meets the framework of possibilities of the visitor over a certain period of time, namely the amount of time visitors have to create their exhibition. The type of investigation carried out in this chapter goes beyond the usual interest in issues such as who visits museums and how often.

I will focus on three concepts a variety of scholars have used to approach the relationship between the exhibition and the visitor. The work of these researchers shares common features such as using qualitative methods and finding an interesting topic that may inspire museum practitioners in their future work.

British sociologists Gordon Fyfe and Max Ross do not explore the museum and the visitor but focus on the informant’s leisure and class consciousness - and then involve the museum’s role in the informant’s creation of social identity [1]. John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking are preoccupied with whether we can actually learn something concrete at a museum and especially how memories of exhibitions are recalled over time.

My approach is to examine how an exhibition is experienced while it takes place and then to add the informant’s reflection-in-action, i.e. how selected visitors at an exhibition talk with and about what they see and experience. Three keywords mark the differences in my epistemological interests in contrast to those of the aforementioned scholars: social identity, learning and experience.

Social identity mediated by the museum

In their article, “Decoding the visitor’s gaze: Rethinking museum visiting”, Fyfe and Ross centre on interpretations of the world associated with museum visits, particularly in relation to class, leisure and place. Their study looks at how identity and structure are mediated by the experiences gained at a museum. They chose to do their study in Stoke-on-Trent in England and randomly selected 15 families to participate. Fyfe and Ross visited and interviewed these families on topics such as their social background, leisure time, lifestyle, community and their relationship to the local area. They are eager to position their survey method in relation to traditional visitor studies, which have been “…one-sidedly qualitative methods, by questionnaire surveys and behaviourist methodologies” (1996:131). They fully agree with museologist Eilean Hooper-Greenhill in that understanding the dynamics of meaning-making at a museum requires, “…a more flexible model of research that moves beyond demographics into interpretive or ethnomethodological understandings and methods” (1988:12).

As a result they did not employ closed-ended questions, but instead invited the families to thoroughly reflect on their lives, also in Stoke-on-Kent, leisure time, social background, consumption and sense of place and time. Although the researchers were interested in finding out how museums are or are not interwoven with the lives of families as consumers of places and spaces, the topic of museum visits was not taken up until an informant raised the subject independently. Out of the 15 families, 35 people were interviewed and Fyfe and Ross’ subsequent analysis leads them to the interesting conclusion that, “museums are good to think with” (1996:148).

In their article they present three of the participating families, but focus specifically on a family called the Cardwrights. The father, 51, has a degree in electrical engineering and the mother, 41, is a teacher, while the two children attend the local primary school. They are a committed family that participates in numerous cultural activities alongside their hobbies and sports. They frequently read books on history and the father has the fundamental belief that life is one long learning process that does not end with school. Their cultural and historical knowledge are drawn together by their interest in local historic buildings and landscapes. The parents have managed to pass on their curiosity about life in the past to their children. Fyfe and Ross explain that, “This curiosity relates to self-identity and empowerment” (1996:143). Exploring/investigating local history means identifying oneself with the past and having the feeling of being part of a story that affects one’s life today. The Cardwrights are good museum visitors, often dropping in on the local museum as part of their education strategy.

Their efforts reflect however more than just a struggle for cultural capital, because the family’s strategy is woven together with the feeling that the local community is being undermined, mainly because influential economic decisions are now made outside of the local area. The Cardwright family has a strong sense of local belonging, but it is not associated with the present. The following statement by a local conservative shop manager that reflects his outlook on the world could easily define them, “…a conservative identification with the provincial commercial virtues embodied in the ethics of traditional middle classes” (1996:144).

The family is glad for the important of things. They see things and places as a sign of a vibrant history that provides the opportunity to disclose grand historical insights to them. They have a romantic view of history filled with emotions, ideas and empathy. They focus on the aura of authentic objects and enjoy what is unique, local and personal about them. They weight e.g. the country higher than the city; traditional shops higher than cheap supermarkets; and handcrafted items higher than industrial products.

When Fyfe and Ross conclude that, “museums are good to think with”, it is not so much the visit at a museum they focus on, as the way the family talks about their life world. Experiences involving class, childhood and school are already part of the museum’s memoirs, which will be discussed and categorised according to what Fyfe and Ross call ‘a museum gaze’.

The fact that Fyfe and Ross did not start their research by asking detailed questions about the actual objects in the museum, the concrete exhibition or the actual learning in an effort to reflect on the visitor’s experience is an exciting and radical starting point. They also do not focus on the individual but the entire family’s experience and relationships. Some of the 15 families participating in the study had never been to a museum or only very infrequently. Their methodological approach describes the museum in the context of family life, as part of their life world, but what they would really like to examine seems a bit peculiar and unclear. At the same time it is also exciting because there is an openness that encompasses both order and chaos.

Learning in the exhibition

Fyfe and Ross look at life world and social identity, but I have chosen to pay closer attention to the exhibition and the learning potential available in museums. More than a decade ago Falk and Dierking published their groundbreaking book, The Museum Experience (1992), introducing their thinking model of the same name. They promote their book as the first one to examine the museum visit with a visitor’s eyes and try to find answers about why people come to a museum, what they do while they are there and what they learn during their visit. In their later book, Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning (2000), they focus much more on learning in the museum, and I want to present their particular concept.

What can you learn in a museum context and what determines this learning? Their constructivist understanding is that learning requires pre-knowledge, proper motivation, a combination of emotional, physical and mental action and an appropriate context in which they can articulate their thoughts. They object to what they perceive as the traditional view of learning at a museum: visitors come to a museum, look at the exhibitions or participate in programmes, and if the exhibitions and programmes are good, the visitors will have learned what the curators and facilitators intended (2000:3). Falk and Dierking perceive this view as a gross oversimplification of what happens.

Their definition of a museum experience as learning is however based on the visitor’s mental attitude:

Museum visitors do not catalogue visual memories of objects and labels in academic, conceptual schemes, but assimilate events and observations in mental categories of personal significance and character, determined by events in their lives before and after the museum visit (1992:123).

Falk and Dierking construct a contradistinction between academic categories and the personal commonsense understanding that ordinary visitors create. Unsurprisingly they believe that the pre-knowledge is of great importance for the visitor’s specific interest, motivation and understanding, but, rather surprisingly, they believe that the learning the museum leads to is actualised until after the museum visit.

The long-term effect of learning is a pivotal aspect of their methodical approach. Falk and Dierking follow specific people at the museum and interview them on the spot. Importantly, they also interview the same people 3-4 months after their visit to find out what kind of knowledge collection the museum visit set in motion. Thus leading to another central aspect, namely that learning beyond the above assumptions “… requires an appropriate context within which to express itself” (2000:32). The research interviews appear to result in an appropriate context in which it is possible to formulate the knowledge in one’s memory and call it forth by using questions and keywords.

The two researchers prefer to explore learning in the museum when visitors come alone or with others in a social context [2]. Their method is to find their informants at the museum entrance, where they do a brief interview about who they are, where they are from, why they are there and what they expect to see and discover. Then they get permission to observe the informants without disturbing them on their way around the museum and make notes in the process. The visit concludes with an open interview about what the informants found interesting and informative. Four to five months later there is a follow-up phone interview.

Falk and Dierking’s epistemological principle is embedded in their model with the three contexts, which combined play a role in the interactive learning that takes place (1992:5, further developed in 2000:12). This model contains the three contexts - personal, social and physical - constructed by the visitor’s continuous interaction during the exhibits.

The personal context can be viewed as each visitor’s own personal agenda and comprises a range of expectations and aspirations concerning what the visitor can get out of a visit. Each visitor’s personal context is unique and contains an infinite number of experiences and knowledge about things in the world, but also knowledge and experiences that differ from the form and content of the museum.

The social context describes how a museum visit always takes place in a social context, because museums are often visited in groups, and people who visit a museum alone cannot avoid coming into contact with or relating to other visitors or the museum staff. Regardless of whether a museum is crowded or nearly empty, it influences the visitor’s experience. Each visitor’s perspective is dramatically influenced by who accompanies them, e.g. by whether it is an eighteen year old walking with an octogenarian, parents walking with their young children or an expert walking with a novice.

The physical context applies to both the architecture, the feeling of the building and the objects within it. How do people find their way to the museum? The parking, wardrobe etc.? How do visitors orient themselves spatially in a museum and how are they met by the design and form of the exhibition? Where do visitors have to go to move around the exhibitions or rest when museum fatigue sets in?

When Falk and Dierking investigate the informant’s experiences at the museum, they see it as a snapshot, but one that is, “… a very long snapshot” in relation to the amount of time visitors spend in a museum (2000:10). They extend this long snapshot even more, because they want to understand learning, which requires “… a longer view”. Panning the camera back in time and space is possible in order to see the learners individually over an extended period of their lives and it is also possible to see the museum in a wider social and local context (2000:11).

Falk and Dierking are particularly focused on the conditions that need to be satisfied for an interactive experience to take place. Both of their books end with concrete proposals for what museum staff can do to improve learning. Their studies are also preoccupied with showing how their model and the thinking behind it can be used, but it is not entirely clear what their informants actually experience.

While Fyfe and Ross operate with the big telescope and look at whether their informants relate in any way to local museums, Falk and Dierking come closer to the museum. They examine what people actually learn in a particular museum. They also clearly address the difference between the immediate linguistic empowerment of the experience at the museum in relation to the linguistic empowerment evident during the telephone interview several months after the museum visit and thereby increase the camera’s pan across time and space in order to get immediate learning incorporated into a larger context. The question remains as to whether they ever get inside the experience of the museum, the exhibition and the objects’ stories.

Falk and Dierking make a tight coupling between learning and memory. What one remembers is what has been learned. They are somewhat unaware that their review process actually helps produce the cues that open the mind. Memory researcher Daniel Schacter writes that memory is not like the photographs in an album, “… we do not store judgment-free snapshots of our past experiences but rather hold on to the meaning, sense, and emotions these experiences provided us (1996:5).

Thus, what is remembered is activated by the cues that initiate the process and these cues may vary and with them also the memories. We may forget and remember depending on, “… the extent to which a retrieval cue reinstates or matches the original encoding. Explicit remembering always depends on the similarity of affinity between encoding and retrieval processes” (Schacter 1996:60).

The unequivocal answer

The focus on the museum’s role in creating social identity and the interactive experiences that create opportunities for learning are approaches that give long, complex answers. The use of qualitative methods and some perhaps rather complex research interests offer many openings and interesting issues, but not as many unambiguous answers.

The use of questionnaires and highly structured telephone interviews can quickly provide pretty clear answer to simple problems. In this way obtaining and comparing the answers about whether the visitors are satisfied with the museum, how often they come to the museum, who reads the signs etc. is easily done. Apart from this kind of research, typical museum visitors in Denmark are notably women aged 50, who live north of Copenhagen and are well educated.

Other researchers have also recorded visitors walking around at exhibitions where they stop to look at something or read, thus providing an opportunity to note what has attraction power and which parts of an exhibition have holding power.

Obtaining simple answers has great appeal, but unfortunately they are also often tied to the small questions asked. Even though visitor studies have been done for decades, various researchers nonetheless believe that little is known about museum experience in its entirety and that the need for further research on the relationship between visitors and objects is great, particularly regarding objects in the context of museum exhibitions (Moore 1997:47, Duncan & Wallach 2004:51).

What really happens in the encounter between the exhibition, objects and visitors? If memory research is credible, every linguistic context that delivers cues like keywords from researchers also creates the answers in that framework, rather than the experience of the museum visitor. Obtaining or finding an expression for the ‘pure’ experience is impossible, as it will always be embedded in the visitor’s previous knowledge, experiences and adventures. In order to understand more fully and concretely how the museum experience creates meanings, other methods besides interviews must be used.

Development of a phenomenological method

Many years ago I came up with the idea that it might be possible to follow museum visitors - then called informants - very closely by providing them with a tiny video camera placed in a hat. Doing so would make it possible to record the informant’s movements around the exhibition, while also recording any conversations that took place along the way. Technically difficult and extremely expensive, the idea was put on the back burner until the late 1990s, when the right technology became more accessible and I was able to have my video-capbuilt [Ill. 8.1].

Ill. 8.1: The video-cap with a tiny camera and the backpack with a video recorder at an art gallery.

The technology is only a small part of the basic methodology, which was developed by doing a number of experiments with different informants in different exhibitions and led to the following ground rules:

- There are always two informants who walk around together [the social context]

- One of them wears the specially designed video-cap that records both the visitor’s movements around the rooms and any conversation between the two people on videotape

- They know they are part of a research project and that everything they do will be recorded and subjected to a thorough analysis

- They are aware that they will be recorded for one hour [4]

- The informants are not asked any questions and control their own conversation.

Falk and Dierking do their observations without disturbing their informants, but my approach is more overt and visible to participants, because it is obviously not an observation of them from the outside. The two informants also create the dialogic space they wish to share with the researcher. They are interrupted and they certainly do a great deal to live up to the role of good museum visitors. Instead of selecting the casual museum visitor, I choose people in advance and agree to meet with them at the museum on a particular day [5].The whole situation is thus strongly influenced by some form of ‘particularity’. Any museum visit can be viewed as an experience which, according to American philosopher John Dewey, is bound in time with a start and an end and the experimental museum visits I set up reinforce this (1958:36).

The informants are not interviewed. The material used for the researcher’s analysis is the videotape with the recording of the visitors’ walk and conversation. In this case, I did ten sequences before I found two informants who were so articulate that they could expand their experiences beyond the simple observation. Doing an in-depth analysis was only possible when I began studying the videotape in an attempt to explore the informants’ construction of meaning. One aspect of the analysis involved discovering their reading strategy, which is the way in which they ascribe meaning to objects and text through their movements in the exhibition and in their dialogue.

Here I will briefly scrutinise three different projects, which focus on the informants’ experience of the exhibitions. One is based on a historical exhibition at the Museum in Copenhagen, the second on an on-line interactive art exhibition and the third is an art exhibition at Sophienholm, outside Copenhagen [6].

Personal cultural history at the Museum of Copenhagen

We are at the Museum of Copenhagen with the two informants, Anne and Rikke. They walk around the exhibition ‘Under the wings of democracy’. From their videotape I initially construct a set of relationships that the informants create internally in this exhibition and externally in relationship to something outside the exhibition space. I find six categories of relationships: knowledge, recognition, perception, internal, external and media relationships. A simple example where Anne sees Carmen Curlers illustrates the relationship called recognition, “My mother had some like these. Do you realise how much hair I’ve lost trying to roll curlers into my own hair. I always got my hair all tangled together and in the end we were forced to cut it off (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:59).

The objects cue Anne to articulate and recall experiences and stories from her own life. One crucial aspect of my approach is finding informants who are articulate about what they see and good at challenging one another. Although we know theoretically that social relations play a role, this does not mean in practice that visitors constantly talk or in a manner that actually reflects their formation of meaning.

Art on the Internet

A study of how users create meaning in three selected web artworks led to further development of the method. The key methodological point is leaving the dialogue between the informant and the informant’s good friend undisturbed. The decision was made to abandon the good friend as the other informant and use one of the researchers as the interlocutor instead. This crucial change in the framework of the inquiry also resulted in changing the ground rules:

- The researcher is included as an interlocutor if desired by the informant in what we call the dialogue process

- The researcher performs what we call a work dialogue after the informant has ‘seen’ a piece of artwork

- When the session is over, we create a reflection dialogue (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:175) [7].

The study of the informant’s creation of meaning in relation to the web artworks involved recording both their body language and other interaction with the works [8]. The overall methodology is called ReflexivityLab (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:136-137, 147-148).

Post museum visit interviews can be seen as a reflection of the visit, which took place some months earlier. The key point is the relationship between time, space and memory. When an informant is in a completely different space, namely at home four months later and talking on the phone about the museum experience, the shift in time and space – away from the museum and original time – is prominent. This situation, where the informant is asked to reflect on the museum experience, can certainly be characterised as a remembrance of the visit. Informants cannot redo the physical visit, but they can change their mental image of the visit.

In the ReflexivityLab the informant is close to the experience because she sits in a space with the work front of her, in the experience situation, and is able to reflect as she looks and uses the artwork. One can call it reflection-in-action (Donald Schön 1983). If the informant in the dialogue is in doubt or wonders about something, she can immediately go back and test her response by going back to the work and repeating the narrative. This means she has the potential to involve her body and her interaction in a new exploration process in the concrete space.

Art at Sofienholm

We are at Sofienholm, where there is a special exhibition on the painter and graphic artist Ole Sporring. The following handout is given out at the exhibition:

A lifelong interest in the Danish humorist Storm P.’s creation of a little comic strip called The three small men combined with a study trip to Arles following the footsteps of van Gogh in 1998 confronted him with these two entities, which normally would not be connected. With a fabulous talent for drawing, Storm P.’s three small men become mediators in his pictures and use paint, make disturbances, lift a corner of the canvas and swing into the lines of the pictures. A surprising and droll clash emerged between the myth of the great artist van Gogh and the busy, active small men (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:79).

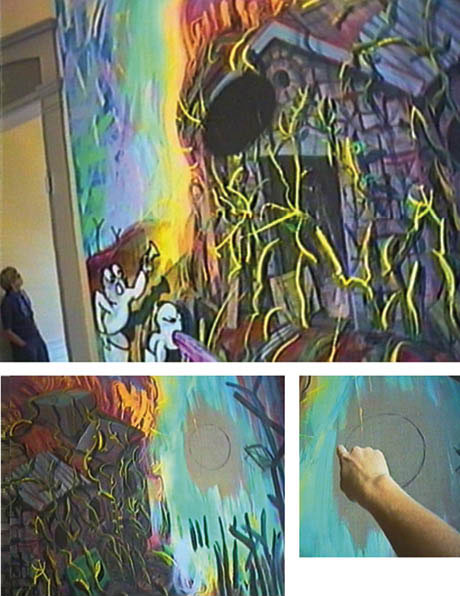

The informant, Jakob (27), who is wearing the video-cap, and the researcher meet to do an experimental walk through the exhibition. The experimental method has been further honed. In their joint dialogue the researcher thinks from the perspective of three categories: the process dialogue, the work dialogue and the reflection dialogue. But where can we draw the line between researcher and informant in a participatory observation? Are the two roles so intertwined that the researcher sometimes becomes the informant and the informant becomes the researcher? [9]

In my role as researcher the inquiry of the visitor’s experience is tied to phenomenological theory, where reality is what people assume it to be (Kristiansen & Krogstrup 1999:14). The researcher’s task is to identify and understand the definitions and interpretations people make; in other words, an essential task for a phenomenological study is to understand understanding (Kristiansen & Krogstrup 1999:16). Creating an empathetic proximity and maintaining a marked distance are both important when doing participatory observation. It can be viewed as two separate epistemological processes in which participation requires empathy for a strange and unfamiliar field and where observation implies a distancing of the observed in addition to the registration of a quantity of factual circumstances (Kristiansen & Krogstrup 1999:122).

Taking a step back here is important. A central point of using the video-cap is that the method can also be seen as an observational study that provides insight into nonverbal behaviour. The video makes it possible to determine the time and space where the informant has been, stopped or passed by. These elementary actions can be used, for example to draw a diagram of the informant’s walk. Using the video-cap also produces some unexpected results, e.g. the recording of head movements when Anne is describing her reaction to the new airport in Copenhagen: “No, no, look! It’s the airport. Have you seen the new one? I was there the other day. It’s completely wild! [At this moment and with these words Anne shakes her head to underline the importance of her expression] It’s really cool. Smashing (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:58)”. Anne shaking her head can either be a physical denial of her verbal testimony, or it can simply be a physical amplification of her unbounded enthusiasm.

When Jakob looks at Ole Sporring’s large paintings, the video shows him using his body to move conspicuously from looking at the pictures exceedingly close-up to looking at them from a far distance. He also has an interesting observation when he looks through the beautiful old doors at Sofienholm Castle and realises that the doors crop the painting in a completely different way, “… so one gets an extra frame. One can have many pictures by using that doorway” (Gjedde & Ingemann 2008:82). Jakob, who works as a guide at the city museum and has recently conducted tours of the Hammershøj home on Strandgade in Copenhagen, makes an external connection to Hammershøj.

The video is a great tool for capturing nonverbal behaviour that might not always be easy to interpret otherwise, because it can be seen and re-seen, because both time and space are caught on the videotape.

The museum’s knowledge and the visitor’s

What kind of knowledge or framework do museums offer visitors? How should this framework be used? Art historian Donald Preziosi believes that the most common gaze is:

… that museums are repositories of unique objects whose principal value is private enlightenment, fetishization, and vicarious possession. You may not be able to own one; you most certainly can’t touch them; but you can if you wish buy a copy of one on paper your existence with what for you can become »a permanent part of your life (2004: 74).

This quote, listed in the Ole Sporring exhibit handout, indicates that there are embedded expectations that visitors are familiar with the great Danish humorist Storm P., his three little men and, of course, the fact that van Gogh lived in Arles and that they have a sense of how these particular paintings are part of the debate about art. Can all of this be counted on as common knowledge among Danes or has the bar been set too high for the ‘ordinary’ museum visitor? Should the museum do something to provide less informed visitors with new insight, or should these details be allowed to slip over their heads? Traditionally, art museums generally adhere to the stance implied in the latter part of this question, i.e. having the right knowledge means being included and a lack of it means feeling on the outside and remaining excluded. This inclusion/exclusion mechanism is effective in maintaining a high-taste discourse.

In the study undertaken here, Jakob, however does not read the handout until after the visit while he eats lunch on the museum’s grounds. What are the experience and knowledge universes brought into play in relation to the artworks and their placement in a narrative? Jakob and the researcher come to the conclusion that being open and tolerant is essential. They do more than just experience something; they create an experience and will always be able to talk about the experience as, remember that time we saw Ole Sporring? (Dewey 1958:35). The experience and memories arouse an emotional reaction that differs in relation to their everyday world and gives them cause for reflection (Dewey 1958:15).

Ill. 8.2: Screen dumps from the walk-video with Ole Sporring’s large painting, “The overgrown house”, 1998. The video camera also records the informants’ hands when they pointing and draw.

The experience the researcher and the informant create contains a duality. On the one hand, the artworks are part of marking what is different, but also mark, on the other hand, a reverse movement of everyday experiences that sheds new light on the artworks. Jakob picks out one of the three small men who, upon turning on a lamp, surprisingly discovers that it sheds darkness and not light. In this instance, Jakob draws on an everyday experience where his two-year-old son tried to shine a flashlight on a sun-filled ceiling only to discover that it did not make a spot of light.

The subtle use of everyday logic, non-art related historical knowledge and experiences run through Jakob’s experience and conversation with the researcher. These aspects of the video-walk are not just something that happen, but are a result of the researcher creating a discursive space that makes them possible and permissible. They are not constantly under a microscope to determine whether they have adequate knowledge of art history to identify all the van Gogh sub-elements that are part of Ole Sporring’s works. They have created a space for themselves where they can be creative and even create an entirely new piece of art. Going up close to a window, they read a sign that says, “House. Various materials and various plants, 2000”. Looking out the window down at the beautiful park, there is a house with a lot of growth and other materials. They think this is quite witty. Entering another room, they look out the window. Surprised to find that there is no sign, they make up their own, “Grass, 2000”. They have adapted the exhibition to an extent that they create their own narratives.

They also create a story about HIM, the painter. They think he is a highly skilled/competent drawer and designer. They are preoccupied by his equilibristic treatment of crude and coarse against fine and light, the sharp and precise against the blurred and wiped off. They see this duality as a riddle waiting to be solved, elevating it to, “... he is just so good”. There is one spot in the exhibition where they give up any attempt to enter into dialogue with him, because the number of drawings is too chaotic and difficult to categorise. Nonetheless, this spot is aesthetically spectacular and contradictory.

Following the informant and the researcher so closely and recording their walk with the video-cap makes it possible to document and analyse their route and dialogue with great accuracy. Analysis of the video indicates that their dialogue takes place within the four dimensions described by Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson in their study, The Art of Seeing (1990):

The perceptual dimension, where there is a focus on the artwork’s organisation and elements

The emotional dimension, where positive and negative feelings and assessments are activated

The intellectual dimension, where cultural and art history are weighted

The communicative dimension, where the focus is on the internal dialogue with the artist.

These four dimensions are the traditional features of a good art history angle, but the surprising aspects of the Ole Sporring project are everything else, i.e. everything that is not naturally associated with the traditional view of what an art experience is. Expanding this field requires using everyday experiences as a framework, or the specific, focused gaze at the design of the experience that brings everyday experiences this aesthetic dimension.

Some of the preconditions for a good informant to enter into a dialogue are that the informant can observe and remain open and obliging. Additionally, the informant needs to be good at taking the initiative and not waiting for the researcher to ask questions or challenge the informant. It also requires that the informant’s language is sufficiently detailed to capture the aesthetic expression in the works and the exhibition design and that the informant has the necessary general education to delve deeply into the possible meaning formations.

If the informant does not meet all these prerequisites, uncovering the richness of possible meaning formation is not possible, but discerning how the framework of possibilities the artwork offers meets the user’s framework of possibilities is. The encounter between the two offers a number of exciting restrictions and distortions that can cause the establishment and confusion of the meaning-making process in both a surprising and constructive way.

With video-cap I focus on the experience and believe that the overall methodology makes it possible to close to not only the individual’s concrete experience and but also to the experience itself in time and space. The video-cap preserves a large part of the physical movement and the three types of dialogue that took place at the exhibition: process dialogue, work dialogue and reflection dialogue. These three types of dialogue are closely related to the experience of the artworks in a certain space. The next layer of reflexivity lies in the analysis the researcher makes based on the videotape and how precisely the researcher’s participation in the process adds to the ability to comprehend what is not stated clearly, but that both people understand. What may seem rudimentary and almost meaningless for an outsider, can be expanded on and given more meaning by the researcher.

The three contexts

The three different epistemological perspectives surrounding the formation of social identity, learning and experience have produced three different methodologies that I hope can inspire the necessary evolution of an essential and interesting field.

Documenting and analysing the large amount of practical knowledge available about the meeting between the exhibition and the framework of possibilities of the visitor is important. As Duncan and Wallach state, “No other institution claims greater importance as a treasure house of material and spiritual wealth” (2004:51).

Notes

[1] Informant denotes the person participating in the video-walk.

[2] In what they call a major study, they do interviews with fifty informants (2000:14 footnote 12) at the National Museum of Natural History.

[3] The video-cap has now been replaced with video-glasses, which show the direction of the informant’s gaze much more accurately. http://akira.ruc.dk/~bruno/Processual/researchingexperiences_x.html

[4] The length of the tape is one hour, but recording lasts as long as visitors can stay focused.

[5] The choice of informants is determined by their qualifications. A draft of the introduction to Gjedde and Ingemann’s book (2008) states, “By using the qualified approach the goal is to find people who have a wide range of competences. For the website and three pieces of web art we looked for two kinds of competences: 1) insight into art, aesthetic experiences, culture, galleries and the like, and 2) experience with computers and familiarity with the use of the web. In addition to using their whole body, we wanted them to have a qualified, differentiated and rich language to express their experience regarding the web art, their inner feelings and their complex memory of knowledge from their personal world and from the culture around them. Using this qualified approach meant that selecting informants was not especially easy. Coming up with candidates, talking to them and believing that the perfect combination of competences had been found can be prove to have been a fruitless endeavour in the hands-on part of the research process. There are good informants and there are the not-so-good informants. What makes a good informant depends on more than just the aforementioned competences. They must also be willing to be open-minded and explorative in the search for meaning in the chaotic situation and material. As a result doing trials with different informants is necessary and material created by not-so-good informants is discarded.”

[6] The Museum of Copenhagen and Sofienholm studies are part of THE MUSEUM_INSIDE project.

[7] In the three forms of dialogue, we attempt to answer three simple questions: 1) How can you create a story based on your interactions and experiences? (narrative construction); 2) Do you see any links to other works? (intertextuality); and 3) Can you connect your experience with anything from your own life? (personalisation or intimacy).

[8] They interact physically with a mouse by pointing on the screen or by moving the mouse. This interaction ‘creates’ the literal work by changing parts of the artwork.

[9] Phenomenologist Alfred Schutz reflects on the time dimension, writing, “He and I, we share, while the process lasts, a common vivid present, our vivid present, which enables him and me to say: ‘We experienced this occurrence together.’ By the We-relation thus established, we both ... are living in our mutual vivid present, directed toward the thought to be realized in and by the communicating process. We grow older together” (Schutz 1973:219).

|